What would Flo do? Use nursing science to improve health and health care

Research Fellow Manu Thakral, PhD, ARNP, describes her vision for moving her field forward.

by Manu Thakral, PhD, Research Associate, Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute

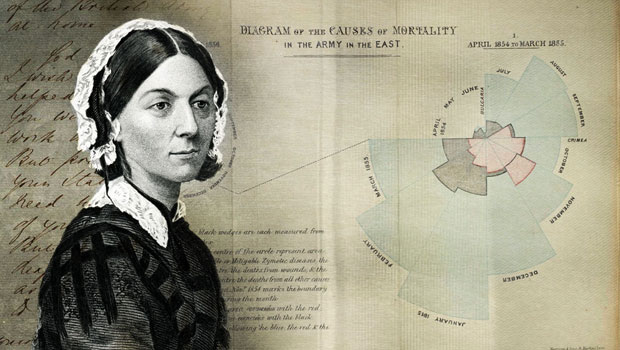

Florence Nightingale is often considered the mother of modern nursing. Indeed, she was a revolutionary figure in nursing practice. She pioneered infection control before germ theory was introduced, founded a nursing school, and produced more than 200 publications. The “lady with the lamp” was also a social reformer and statistician — and more than anything, a scientist. She was the first to discover how the physical environment of the hospital affected health outcomes and how good nutrition improved healing of wounded soldiers. As the first nurse scientist, she addressed a public health crisis and lobbied for health policy changes to improve conditions and reduce risks, setting the stage for future generations of nurses.

Flo, as I imagine I would call her if we ever met, is a hero of mine, as she helped define the comprehensive and crucial role that modern-day nursing still holds. Today’s nurses work in quality and safety, leadership, education, and evidence-based practice, to name a few. Of the multiple conceptual models that define nursing, there are always three common elements:

- person,

- health, and

- environment.

These elements are interrelated and can’t exist without one another. Therefore, nursing care is dependent on an understanding of relevant contextual factors, which could mean a physical space, medical history, or even a personal attitude.

A unique perspective on health disparities

This basic philosophy not only applies to nursing practice — but to research as well. One example is my work over the past two years at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI), where we’ve been addressing a serious public health crisis: the opioid epidemic. Our team evaluated clinical initiatives to change prescribing practices — steps that were proven effective at reducing doses for patients using opioid therapy to manage chronic pain. Nurse scientists are in a position to study the social and structural inequalities that result in health disparities and find ways to improve health equity in our community. So I was particularly interested in finding out whether dose reductions were consistent across different groups of patients, like those with mental health conditions or history of substance use. My heightened awareness of personal and environmental factors that could potentially play a role in which patients were selected for dose reduction allowed me to make a unique contribution to our interdisciplinary research team.

In a broader context, questions such as these are about health care equity. Flo was a visionary and a steward of social justice. She fought for equal access to hospitals for patients of all faiths and those with mental health and chronic conditions. She also collected empiric evidence to support her advocacy efforts. In today’s uncertain political climate, the risk for health disparities among vulnerable populations is high and the need for evidence-based solutions is great. Here in Washington State, older adults and people with disabilities, especially in rural counties, are at higher risk for social isolation, less opportunity for employment and education, and barriers to health care access. Demographic shifts in the coming years will only increase those risks.

Kaiser Permanente, with its strong commitment to the health of entire communities is a particularly promising environment for nurse scientists to study such issues. For one, researchers here have access to comprehensive data on large populations as they get their care in real-world, community-based settings. Also, the organization expresses strong support for the 50,000+ nurses it employs. According to its National Nursing Research and Evidence-Based Practice website, Kaiser Permanente is committed to maintaining and reigniting nurses’ passion for science and discovery by conducting original studies and reviewing published evidence to inform and improve practice. It also commits to documenting and communicating the value of nursing research; the systematic and rigorous study and evaluation of nursing practice and nursing-sensitive indicators; and the impact of nursing on patient care and resulting outcomes.

Opportunities abound

From my perspective at KPWHRI, opportunities for nursing research are plenty. Examples include:

- Evaluation of telephone-based nursing services: As the physician shortage grows, nursing practice is becoming more independent, especially in rural community health settings. Registered nurses are taking on more responsibility for wellness visits and telephone consulting nurse services are highly utilized. In fact, consulting nursing services at Kaiser Permanente Washington are now treating 15 conditions independently over the telephone using computer-assisted structured treatment algorithms. Nursing leadership is interested in answering the following questions: Are there differences in patient outcomes from those who call consulting nurse services compared to calling nurses at primary care offices? Can we find those differences using electronic data that we can gather from health records or do we need to use more sophisticated programs to analyze what is written in notes within the records? These questions could be the first step in understanding the role of ambulatory nursing in protecting patient safety and how to use electronic data to support nursing research.

- A randomized trial recently conducted by the women’s health research team at KPWHRI in collaboration with the University of Washington School of Nursing indicated the effectiveness of telephone-administered cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) among perimenopausal or postmenopausal women. This work led to another collaborative project that will be the largest ever telephone-administered CBT-I trial for older adults with chronic pain and insomnia. This intervention supports a non-pharmacological approach to symptom management and reduces barriers to health care access among vulnerable populations in rural counties.

Contributions may also include:

- assessing and evaluating the impact of nursing care on patient outcomes in ambulatory care settings using innovative methods and metrics;

- better understanding the experience of patients living with chronic conditions and testing innovative interventions to address symptoms that have a significant impact on quality of life with a focus on populations vulnerable to health disparities;

- facilitating key collaborative relationships within and outside Kaiser Permanente and engaging local universities and community-based organizations to provide both scientific expertise and understanding of broader social constructs that contribute to health and health disparities;

- providing opportunities for increased clinician involvement in designing and disseminating research through education and mentorship.

An ambitious list? I suppose so. But I think Flo would approve.

Do you have thoughts on how to move the field of nursing science forward — here at KPWHRI or elsewhere? If so, please leave a comment below or reach out to me personally at thakral.m@ghc.org.

Fawcett J, Watson J, Neuman B, Walker PH, Fitzpatrick JJ. On nursing theories and evidence. Journal of nursing scholarship. 2001;33(2):115.

Learn more about Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. Sign up for our free monthly newsletter.