The House of God at 40

We can still learn from a 1970s novel based on real-life doctors, Dr. Eric B. Larson writes, recalling his internship time with them

By Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute

executive director, and Kaiser Permanente vice president for research and health care innovation

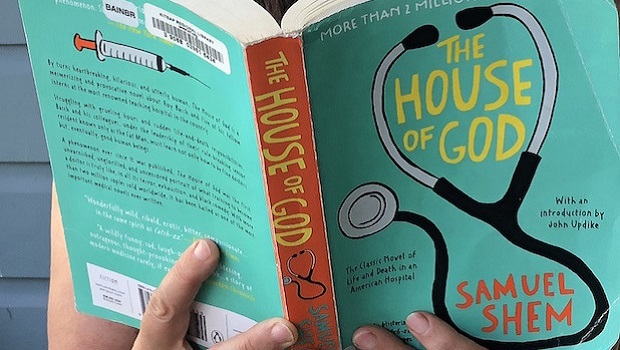

We just marked the 40th anniversary of the publication of The House of God, a classic book about medical training. Named one of the 10 best satires by Publisher’s Weekly, at number 2 after Don Quixote and before Catch-22 at number 3, the book has sold more than 3 million copies since its release in 1978.

Countless medical students and other clinical trainees have read The House of God and it’s been discussed at numerous literary criticism events. It was described in The New York Times as “raunchy, troubling and hilarious.” And it’s about my 1973-1974 medical internship.

The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) just published two commentaries to celebrate 40 years of The House of God. One is a reflection by the author, Stephen Bergman, MD. The other is a physician’s appreciation. I reread the book when the JAMA pieces came out. Today, I find it shockingly dark but irreverently humorous. It reflects the “revolutionary” spirit and excesses of the time, with the Vietnam War ending and Watergate scandals beginning. Like all great satire, the book rings true, even with its gross exaggerations. And Bergman’s witty, sardonic perspective and somewhat self-absorbed style can still be entertaining after all these years!

But what’s not funny about The House of God are the inefficiencies, harmful overuse, and inhumane treatment of older, demented patients that the book exposes—abuses that unfortunately still happen in health care today.

Sam (Steve) and our class of residents

Bergman wrote this semi-autobiographical work of lightly disguised fiction as Samuel Shem. I know him as Steve, my friend, colleague, and classmate at Harvard Medical School and in Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital internship program. The House of God describes a group of interns (a position now called R1, for residency first year) at a major teaching hospital in what was supposed to be the most desirable internal medicine training program of the day. The setting is clearly our program, although book reviewers at the time suspected the hospital involved was in their city of New York, Newark, Houston, or Los Angeles. I’m not sure why anyone wanted to be associated with the site as it was portrayed. The book’s description of the hospital’s high-stress atmosphere and the arrogance of its leaders and attending physicians is so devastating that it enraged everyone (at least those in authority!) who thought they were depicted.

When Steve was drafting this, his first novel, six or seven of us from the program would get together and share liquor and stories about our daily lives. As Steve ran a tape recorder and took notes, we talked about 100-hour weeks and the impact that stress had on the care we offered our patients. I saw drafts of the book as Steve wrote it and progressively toned down his anger and annihilating content, possibly to avoid getting sued, so the story goes. Since our internship, some in the group have occasionally gotten together, most recently in December 2018 for a panel discussion about The House of God at New York University Langone Health. I’d say all of us in that small group of wounded warriors have mellowed a bit.

Truths from fiction

The characters—we interns—witnessed mind-numbing overdiagnosis and overtreatment, especially for people late in life who didn’t want some therapies and clearly did not benefit from them. The book depicts the excesses of fee-for-service practice and hospital care, when hospitals and doctors were paid by the procedure, not by their patients’ health, so they were rewarded for providing more.

I am glad to say things have gotten better for patients and medical trainees since 1974. Hospice and palliative care were virtually unheard of in the days of The House of God but are much more mainstream now. In my own practice, I learned, sometimes the hard way, the value of the great new medical movement of “less can be more.” Patient-centeredness and shared decision making are among other themes that were not part of the clinical vernacular, let alone practice, in my internship days.

Yet, I’m aware that we still face the challenge of often providing too much care in instances when “more seems better,” especially near the end of life. This issue is especially common in fee-for-service medicine, especially to very old people. These ongoing challenges are the echo of the past that brings me to the present. I now find it inspiring to be working in a nonprofit integrated health care system, Kaiser Permanente, where our goal is to provide appropriate care for all. I’m encouraged by professional organizations such as Choosing Wisely, which advocate for high value and excellence in service. And I’m continually energized to be collaborating with other health scientists and clinicians on research that seeks to turn the tide on problems of overuse, inefficiency, and associated harms in medicine.

Re-reading The House of God after all these years made me realize that this call to fix faulty systems is what drew me and many of my internship classmates to medicine in the first place. Looking forward, I see that our profession has made progress, but we must persist in our efforts to fully achieve the needed improvements.

Learn about preventing overdiagnosis and overuse from the JAMA Internal Medicine series “Less is More” and Dr. H. Gilbert Welch’s book Less Medicine, More Health. Dr. Welch will give a seminar at KPWHRI on September 24, 2019.

kpwhri leadership

Change and constancy in a time of transition

Dr. Eric Larson reflects on KPWHRI’s incoming leader, the institute’s accomplishments over time, and its sustaining values.