New Lancet report offers hope for preventing dementia

Dr. Eric B. Larson, a report contributor, answers questions about reducing risks, disparities, and threats from COVID-19

The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care published a report July 30, 2020 that highlights recommendations for policy makers and individuals to help reduce dementia risk worldwide.

Eric B. Larson, MD, MPH, senior investigator at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute (KPWHRI), is among 28 internationally recognized dementia experts who contributed to the comprehensive report. Here, he answers questions about its significance and the ways KPWHRI research on aging addresses issues raised.

Q. Researchers publish a lot about dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Why does this report draw attention?

It summarizes current knowledge in a way that’s remarkably complete—everything from prevention to biology to treatment to care. And it provides a social context that’s not just focused on high-income Western countries. Contributors included researchers from Africa, the Middle East, the Asia Pacific region, and elsewhere.

Also, this is a time of new discovery. With our populations aging, we can now see things that were never possible to see before, simply because there weren’t enough people over age 90 to study. But now, for example, we have numbers of people over 90 who have features in the brain that were once associated with Alzheimer’s disease, but these people are not demented. Understanding resilience has been one focus of our ACT study of older Kaiser Permanente Washington members for the past 10 years or so. This report goes into that question in a way that’s very informative.

Also, we wrote in this report about the impact of COVID-19 on people with dementia.

Q. The Lancet Commission published a comprehensive, landmark report on this topic just 3 years ago. Is it unusual to follow-up so soon?

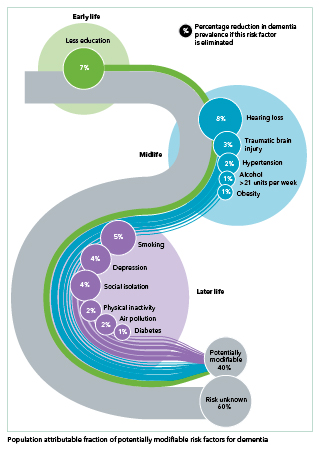

Yes, but our understanding of dementia has grown remarkably. For example, we added 3 risk factors to the 9 in the previous report. The newly identified factors are 1) traumatic brain injury in mid-life, 2) exposure to air pollution in later life, and 3) excessive alcohol use, defined as more than 14 drinks a week. (The other 9 are less education, hearing loss, hypertension, obesity, smoking, depression, social isolation, lack of physical activity, and diabetes.)

There’s a figure in the report that shows all 12 risks across the life course, and how much the reduction of each factor could potentially reduce the prevalence of dementia in the world. Taken together, theoretically up to 40% of dementia cases could be prevented or delayed by modifying all 12 risk factors. This is up from the 35% we reported in 2017.

Q. Did that increase inspire your group’s statement that "we find a hopeful picture"?

Yes. We’re finding increasing evidence to support efforts for prevention. For example, wearing a hearing aid if you need one can make a big difference. It may be the highest modifiable risk factor—with the potential to reduce rates by 7%, according to researchers from the University College London.

Other issues are not so simple to address. They involve complex behaviors that are a difficult to change. They also involve social determinants that require large-scale policy changes. But the pay-off could be great. The report states: “[C]ulture, poverty, and inequality are key drivers of the need for change. Individuals who are most deprived need these changes the most and will derive the highest benefit.” Making early childhood education more available is one example. Many lower- and middle-income countries don’t have the resources for this. We see the rates of dementia are actually increasing the fastest in these poorer regions, whereas, in higher-income countries, rates are going down.

So, for the best return on our public health investments, we must address caring for the people who are at the greatest level of need. So, for instance, to reduce the worldwide burden of dementia, we need to support the development of better schools in lower- and middle-income countries and provide education for girls and women in places where that’s previously not been allowed.

Q. What about in our own country?

The need for improvement is significant. Just look at the list of risk factors and think about who’s most affected. Think of disadvantaged groups in our country who don’t have access to good, early education and nutrition, which are needed to build brain reserves during growth and development. Or the disproportionately high rates of hypertension in our Black population. And who is less likely to have access to good care for such chronic conditions? Which populations have higher rates of smoking and live closest to high-traffic areas with lots of auto exhaust? Who has a greater chance in old age of social isolation? All these risks disproportionately affect lower-income people in disadvantaged, marginalized groups. So, in general, individuals who are most at risk will derive the highest benefit from individual and population-level changes that reduce risks. More research and policy changes are needed to address these disparities.

KPWHRI is doing work to better understand and address disparities and other social determinants of health in areas such as care for obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and mental health. Our MacColl Center continues working in safety net community clinics to strengthen primary care for disadvantaged populations. And we have several new proposals in the pipeline to address racial disparities in care. In the next phase of our ACT study, for example, we are proposing to oversample certain groups so that we can research a more racially and socioeconomically diverse population. All this work that’s aimed at improving health of at-risk populations over the life course can eventually move the dial at preventing dementia in large populations.

Q. And what about research to help individuals address their own risk?

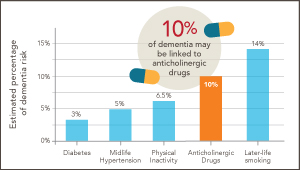

We’re doing some exciting work in these areas as well. One example is the SMARRT study, where we’re pilot testing the effectiveness of personalized interventions for older people who are at high risk for dementia. Participants work with coaches to make behavior changes that address the modifiable risks—issues such as, blood pressure control, risky medications, diet, physical activity, and social isolation. Other research includes studies to reduce sedentary time, prevent falls, improve drug safety, and measure exposure to air pollution.

Q. There’s been a lot of news recently about an easy-to-use blood test to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease. Did the Lancet Commission take a look at that, and if so, what are the implications for research and patient care?

The findings that were published this week in the Journal of the American Medical Association and widely covered in the press were not available when the Lancet Commission completed our report, but I think these results are intriguing. They raise a lot of questions, ranging from the fundamental nature of Alzheimer’s disease to whether the results extend to everyday populations. It’s likely to take several years before the test becomes widely available and even then, we’ll need to figure out what role a test like this might play in practice. A simple blood test will be more acceptable to patients than other diagnostic procedures such as spinal taps or expensive brain imaging tests.

Q. The report also addresses care for people with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Is there practical information for family members and caregivers?

The death rate is extremely high for people with COVID-19 who have dementia and are living in living in nursing homes. Tragically, it may be as high as 50% to 70%. One reason is that infection is easily transmitted in these congregate settings. But probably more important, these residents are often very old and have other chronic conditions, such as heart failure and kidney disease. The two factors together probably just shorten a person’s survival.

Unfortunately, the common response has been, “Let’s just lock these facilities down; we won’t let anybody visit.” That results in social isolation and misery, especially when a person with dementia doesn’t understand the need for social distance.

Our report recommends ways to make these homes safer, such as providing better equipment and infection-control training for staff members. Also, better pay and sick-leave for care-home workers may help by encouraging staff to quarantine when they might be infectious. Better testing among staff and residents is also needed, as well as strong efforts to keep staff and residents from moving among facilities and spreading the virus. The report also calls for changes to allow more intensive COVID treatment, such as oxygen therapy, to occur in care homes, limiting the need for hospitalization that increases risks.

Overall, the 2020 report suggests a way forward, building from expanded international research and offering hopeful ways to reduce the burden of dementia through prevention and better treatment—including confronting the COVID pandemic and rising disparities.

medication use

Could ‘deprescribing’ anticholinergic drugs prevent dementia?

Dr. Larson reflects on splashes, ripples—and new research by U.K. scientists, which builds on his earlier findings from the ACT study.

caregiving

Training for caregivers of people with dementia: How to scale up

Dr. Rob Penfold leads pragmatic trial of new online version of proven program developed by UW colleagues.

act study

The science of aging brains: ACT collaborations grow

KPWHRI and UW program continues to be a rich resource for researchers studying resilience and ways to avoid Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.